It is time of elections: A view from New York!

India’s General Elections 2019 is here!

We are in the middle of it all. We are surrounded by the hustle and bustle of campaigning, we are getting nearly drowned in the promises and rhetoric of the people who are in the fray. But our sights and views are constrained by the hills in the east and by the oceans in the west. The sounds we hear mostly emanate from the shouts and yelling of local candidates and his/her supporters. Most of us never bother to fathom the scale of the efforts, the sheer magnitude of the official work that goes behind it, the number of official personnel involved in its execution.

Here is an extract from a report by an outsider, a reporter of New York Times, which may put the total picture in perspective (read the full report HERE).

What It Takes to Pull Off India’s Gargantuan Election

More than 900 million people — over 10 percent of the world’s population — could head to the polls over several weeks. The government is committed to polling every voter, no matter how isolated. Democracy doesn’t get much simpler than one person, one vote. But what happens when that one person is a hermit living alone in a jungle temple surrounded by lions, leopards and cobras, miles from the nearest town?

Bharatdas Darshandas, the lone inhabitant and caretaker of a Hindu temple deep in the Gir Forest, has become a symbol of India’s herculean effort to ensure that the votes of every one of its 900 million eligible voters is counted. Voting began Thursday in the world’s largest — and arguably most colorful — democracy and a team of five election workers will trek to Mr. Darshandas’s temple and set up a polling station solely for his use. “It is an honor, it really is,” Mr. Darshandas told reporters following a general election in 2009. “It proves how India values its democracy.”

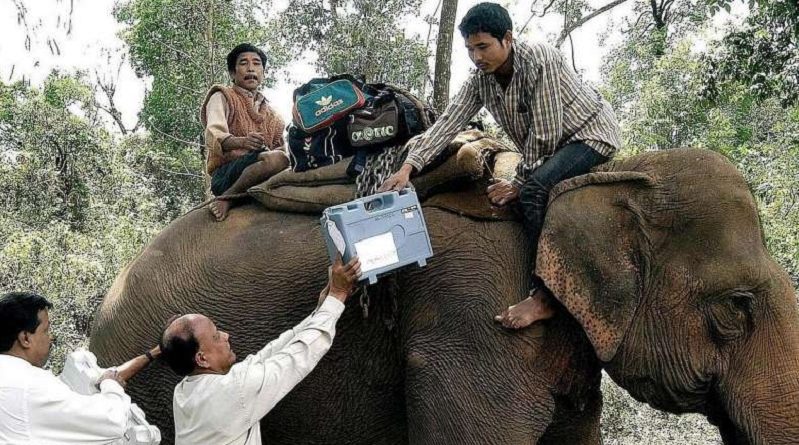

In seven phases over 39 days, as many as 900 million people will cast ballots nationwide at a million polling stations, spread across densely populated megacities and far-flung villages. Each phase lasts a single day, with the date varying by location. It is a feat of gargantuan proportions, requiring 12 million polling officials and cutting-edge technology. But just getting to the voters — some of whom live among the world’s tallest mountains, its densest jungles and sweltering deserts — presents its own set of challenges. To provide ballots in the most remote areas, the politically independent Election Commission of India will deploy 700 special trains, as well as boats, planes and teams of camels and elephants.

“There are mountains which can be reached only by helicopter,” said SY Quraishi, author of “An Undocumented Wonder: The Great Indian Election” and the country’s former chief election commissioner, who listed the many means poll workers use to get out the vote. “In fact there are many areas so remote where none of these will work, then parties have to walk for three days.” Among those remote locales is the country’s highest polling place — 15,256 feet above sea level — found in a village in the Spiti Valley of the Himalayas, where just 48 voters live. Election officials have to not only account for the most isolated voters, but also provide efficient systems for those in the country’s teeming cities. The busiest polling stations will see as many as 12,000 people arrive to cast votes.

In addition to the poll workers, tens of thousands of troops are deployed throughout the election to prevent party activists from interfering in the process and subdue potential outbreaks of violence.

How do you count 900 million votes? The tool most credited for improving the ease with which Indians vote is also part of the reason the process takes so long. While voters in the United States and elsewhere continue to argue the merits and security of electronic voting, India has been using secure electronic machines since 1999. Beginning in 2014, the government introduced a second machine, a printer that deposits a hard copy of each ballot into a sealed box, ensuring an additional layer of redundancy and security.

While voters in the United States and elsewhere continue to argue the merits and security of electronic voting, India has been using secure electronic machines since 1999. Beginning in 2014, the government introduced a second machine, a printer that deposits a hard copy of each ballot into a sealed box, ensuring an additional layer of redundancy and security. Though nearly a billion people could cast ballots, there are just 1.63 million “control units,” the computerized brain of the electronic voting machine. The machines are toted across the country for use during each geographic phase of the election.

But more than 8,000 candidates representing more than 2,000 political parties are vying for 543 available seats in Parliament’s lower house, the Lok Sabha. To secure a majority, a party or coalition must control 272 seats.